1. Introduction

Humans are evolved animals and so to understand how humans work we must look to the evolutionary process. The religions were early explanations for how life came into existence but now we have science. The first explantions relied on faith whereas science uses logic. People who choose evolution over religion take an evolution path in life. Many scientists claim to be spiritual but not religious. They have an awe and respect for the physical and biological world around them. They have no need for rebirths or afterlives. They see life as it really is and are content with that.

I was fascinated with evolution from an early age and it has dominated my life. I travelled widely, including working in Papua New Guinea for eight years. Below is a memoir of travels and observations in an attempt to understand life (of about 30 pages). In these memoirs I include the ideas of genetic and cultural evolution.

There are also a number of drop down menus which contain short stories from my own experience in “Stories”, stories from earlier colonial books in “Snippets”, and other philosophical ideas in “Philosophy”.

2. Travel

With large smiles and beaming faces two monks in saffron robes sat opposite me. One was about middle age and the other, the leader of the two, maybe ten years older. The long narrow boat rocked gently on the Mekong and the green jungle formed a wall on either side of the river. Every ten kilometres or so a small village cut out of the jungle would break the monotony with women carrying goods on heads, tethered buffaloes grazing the thick grass and occasionally children splashing near the river’s bank. Naturally talkative, I couldn’t resist any longer. Luang Prabang was several hours away so what an opportunity for a long conversation. I wonder if they spoke English?

They did, the older better than the younger. They seemed as happy for conversation as I. After some casual conversation on where we were going and from where we had come, I asked why there seemed so many young Buddhist monks in Laos? They explained that only monks go to heaven and so young boys became monks for a year or so and then left to go about their normal lives. This gave them entry into heaven. What about women then? They didn’t go to heaven but possibly could if they were reincarnated as males, but they were not sure on this point. As I plied them with questions both monks, and the older monk in particular, came easily with their answers saying that the main thing in Buddhism was fate or destiny. You are born, a reincarnated non-material soul enters your body, you die, and the soul moves on to some other body, not necessarily human. Fair enough, I understood that, but then where does evolution come in? Surely there is some conflict here as evolution tells a different story. Both grinned widely. I could see that their confidence in their beliefs was so deep that it was pointless to go on. Enjoy the moment. I parted best of friends with even an invitation to visit their monastery. I asked them If I could use their picture in my text.

Years earlier, when I was in Chiang Mai, the main Wat was having an open day for people interested in Buddhism. Monks of all ages looked splendid in their rich yellow robes. The grounds were freshly swept. The colourful flags were flying. The temples that dotted the large grounds, many hundreds of years old, had an air of authority. Great wisdom had been accumulated. The mechanism of the world was known. I was desperate to be part of it. But why did they teach me evolution at school and spoil it all? There was a row of seated monks and westerners could ask them questions. I asked several about evolution but no one knew of it. I was reminded of my first week at university when I was handed a questionnaire. One question was “Would you rather be less happy and know the truth, or much happier and not know the truth?” I blame this single question for ruining my life. I found out later that the majority would rather be less happy and know the truth. But these were university days with students setting out to expand their minds and whether this applies to older people I don’t know.

In my early twenties I was interested in Indian religions and a friend of mine took me along to films of Krishnamurti speaking at the local Theosophical society in Adelaide. I have never been religious myself but curiosity about what other people believe and why they believe it has led me down many different paths. Jiddu Kristnamurti was one of two brothers “discovered” by Annie Besant walking on a beach in Chennai. Annie was leader of the Theosophical Society at the time. She set him up as leader of the “Order of the Star in the East” and he gave talks around the world. There was even a temple built at Mossman, Sydney in 1923 that seated two thousand people. But he himself saw that the beliefs of the Theosophical Society were devoid of substance and disbanded the Order of the Star and went off on his own. He wrote some fifty books. His writings are similar to Bertrand Russell, with a very matter-of-fact, no-nonsense approach. He said that life is a “pathless path” and that each person must come to his own realisation through his own thoughts and not rely on the teaching of others. He was spiritual but not religious.

Decades later I found myself staying at the Krishnamurti Centre in Chennai. It had a large central hall on park-like grounds. The hall had a library upstairs with many books on Indian religions. Surrounding the hall were satellite buildings set up with guest rooms. It was a beautiful place. On the other side of the hall was the kitchen and all the meals were vegetarian and quite tasty. It was free to stay there but you could make donations. It was run by another man of the same name but unrelated as Krishnamurti is a common name locally. Some thirty people from all over the world were staying when I was there. This type of environment led to many conversations on religion, reality and existence.

After I moved to the Theosophical Society, also in Chennai, a short distance away on much bigger grounds, which included kilometres of sea frontage. Here I read the works of Blavatsky, Besant, Leadbeater, and so on. But this society is lost in the past and the world has moved on. There was little interest to be found here. The society had an abandoned feel. Its wealth came from the past. The glory days were over and it struggles worldwide for members.

I next went to the Sri Aurobindo and the Mother’s ashram, Auroville, just outside Pondicherry on even bigger grounds. The “Mother” was Aurobindo’s partner and she was of Egyptian origin. This community was so big that it contained its own villages and you needed to hire a motorcycle to get around. There was even one village called evolution. There were some four thousand devotees living there when I stayed with more than half being French (Pondicherry was a French enclave), then German, then a mix of other European nationalities as well as Indians.

There was a huge ball twentynine metres high called the “Matrimandir” covered by gold discs that was still being constructed. Up the top was suspended another ball which was used as a meditation centre. I once tried to meditate there but gave up as I was bitten by too many mosquitoes. I also gave up on the written works of Sri Aurobindo as I found them indecipherable. I spoke to many people but I found few had read Sri Aurobindo’s works, or if they had started, not lasted long. But the community is a success. It is growing. It started as about twenty square kilometres of degraded land and its rehabilitation included planting with cashew trees and these now line many of the community’s dusty roads.

There is an interesting restaurant in Auroville called the “solar kitchen”. Here I met an academic Malaysian who was wandering the world. He told me that the Kaaba was an earlier shrine to various gods and goddesses such as Hubal and al-Lat and was made of bricks without a roof and contained in its wall a meteorite. It had nothing to do with Islam as this religion had not yet been invented. Muhammad later pulled it down and rebuilt it with a roof. As I had read a little Islamic history we had some good conversations. I asked him if his travel could lead to his changing his mind and adopting new ideas. He said that regardless of what he chose to believe, he would be rejected by his community if he went back with different ideas. He grew up with Islam, it was his habit, and it was too difficult to change this late in life. And if he did change his ideas, he could never admit it.

Several years later I stayed at Auroville again. It is now more of a community than a spiritual centre. I also stayed again at the Krishnamurti center. In all I made some seven trips to India traveling to spiritual places such as Puri, Rishikesh and Varanasi, as well as other general travel in India. The ideas of the world are many and varied. Are some right and others wrong? Are they all partly right? Are none of them right but simply early guesses on how the world works?

3. Evolution

At university I studied engineering mathematics and biology and after a year of writing software in Melbourne I was offered a transfer in the same mining company to New Guinea which operated a copper and gold mine. My interests extended to the philosophy of biology, and evolution in particular. I read everything I could get on the subject. But I also knew that there was little chance of employment in this area so I had to be practical and engineering seemed as good as anything. I was glad to leave cold and crowded Melbourne for a new adventure. I started diving when I was eighteen and I knew New Guinea had a great reputation for wreck diving.

In terms of understanding, evolution was the newcomer. What chance did it have? The older religions were Goliaths by comparison. When evolution burst on the scene with Darwin’s On the Origin of Species in 1856, the existing religions attempted to suppress it. They are still suppressing it today, with some worse than others. Some deny it outright while others try to accommodate it. Pope John Paul, a modernist compared with his predecessors, said that we did have evolution but when Homo Sapiens came into existence, God inserted a soul.

I stayed in New Guinea for eight years. Some of the experiences on this hot, humid and jungle-covered island were very powerful. I dived two or three times a week, mostly at night, and had various other miners as dive buddies. One was a geologist. Bougainville was mountainous and one hot weekend morning we went for a swim in a mountain pool. A strong stream ran through it and the water was clear but not cold and some twenty kilometres away, you could see the sea. The reason why the view was so good was because at the other end of the pool, there was a waterfall with a drop of some fifty metres onto rocks below. This drop allowed a clear view over the jungle. Few people ever came here as machetes were needed for the long walk and also because of the danger of being washed over the edge. But it was safe provided you stayed in the top half of the pool. There was an imaginary line that we all knew and if we went over this line, regardless of swimming ability, the current was too strong to make it back to safety. The geologist had recently separated from his wife and we thought this swim might relieve his depression. To our surprise he kept swimming near this line but not over it. We forgot ourselves and splashed around and all of a sudden the geologist realised he was over the line. He was a good swimmer but to no avail. The mine helicopter retrieved his body that afternoon.

I don’t put this incident in lightly and it haunts me to this day. But it shows how intricate the struggle of ideas in the mind is. The mind is fickle and at any moment it can change direction. The struggle for survival is not as strong as we think. We have an instinctual fear of death but play with it. Was it suicide or bad luck? We will never know. The decision on where to swim in the pool must have involved both genetic and cultural ideas. But what are these “ideas in the mind”? The fear of death is one of them. Books on evolution use words such as innate, instinctive and inborn. To me, these seemed all the same and could only be the genetic side of us. The chemicals produced by the genes include proteins and hormones and these run the body. For simplicity in the text below, I will use the terms “genes” and “genetic” to represent the chemical mechanism of the body. (If in doubt see Bergland, R., 1985, The Fabric of Mind).

Just as people vary on the outside in their height, appearance, expressions and mannerisms, they must also vary on the inside. I remember the bell curve of people’s heights at school with the average in the middle and the graph falling away quickly on either side. Inherent characteristics such as fear, ambition, love, hate, envy, and jealousy, must also have a genetic component, and the strengths of these characteristics would vary between people as per bell curve. These emotional states are genetic and have evolved to improve the chance of survival. We are different both externally and internally. I suppose this difference is what makes everyone unique.

Now comes the interesting part. It seems that genes use a “reward and punishment” approach to direct the actions of the body towards survival and so eventually reproduction. You feel good when you eat food and bad when you don’t. Finding shelter, keeping warm, producing a family, and so on, all increase your happiness. Love evolved to keep couples together and compassion and empathy to make sure children are cared for. Genes guide us towards reproduction by reward and punishment. The genes are part of our makeup. We can not change them but we can modify and repress those parts of the genetic we don’t like. For example, the fear of heights (genetic) can be partially overcome by taking up some activity like rock climbing (cultural).

Seeking happiness and avoiding pain is the method of all animals with developed brains. Hormones that produce happiness include dopamine, serotonin, oxytocin and endorphins. By correctly addressing the genes these hormones are released in the brain. This is true for all animals including humans. But where the volume of cultural ideas becomes large, it is possible to cheat the genes in their purpose of reproduction. Examples could be artificial sweeteners that give the reward but not the nutrition or contraceptives that allow pleasure without the genetic consequence of children. Caffeine in tea and coffee has no nutritional value but many people enjoy it. Some people today limit family size and opt for more holidays and leisure. Happiness can become addictive. Those most desperate for happiness bypass the genes altogether and take opiates or other drugs that directly mimic the natural happiness hormones. As cultural ideas grow in volume, we appear to be moving away from reproduction as the main goal in life to pleasure with limited or even no reproduction being the main goal.

This same method of reward and punishment applies to most things, both genetic and cultural. Governments reward you for exemplary behaviour (medals, awards, titles, and so on) and punish you for behaviour they disagree with (fines and prison). Businesses promote you for hard work and fire you for laziness. Universities give you a degree when you study and fail you when you don’t.

Rewards can be complicated so people look for net happiness by taking in those cultural ideas that they believe will best address their genetic ideas. A person may endure a boring job only because of the necessity of feeding children that is thought to be the greater good. Here genetic nurturing plays an important role and a later happiness is predicted from successfully raising one’s children. A person may work grudgingly at passing exams only because happiness in the form of a better job is hoped for in the future. Here the genetic desire for status and success is important. A priest may go without in this world in the expectation of greater merit in an afterlife. Here a belief in life after death is necessary. In all cases the path taken is still one of maximising happiness in the long term.

However, with the geologist above I like to think that a mistake was made in the pool. But he increased the chance of a mistake by going close to the line. The mind is capable of mistakes and, as well, there is an element of luck in life. We might decide on a trip to the seashore but strong wind or rain may ruin the experience. We may enroll in a course to improve our education but find it poorly run. We may go to a restaurant for a nice meal and get food poisoning. So while our happiness goes up and down, there is still a genuine attempt to make choices that improve our lot.

I remember a trip to Myer’s reef some four kilometres offshore with four friends from the mine. It was a true reef but did not break the surface as even at high tide it was two meters below the waves. And waves there were aplenty as the reef interrupted the natural flow of water causing chop. Indeed, that was the method of finding the reef; look for the disturbance. The currents were strong and the reef was the top of an underwater mountain that fell away precipitously for hundreds of metres into the black depths. The reef was attractive because animals had to swim around or over it and by sitting on the edge, two or three meters down, holding on to chunks of coral, one could observe all the large fish coming up from the deep. Being so close to the surface, little air was used so we could stay for hours. The water temperature was twenty-eight degrees, and it was getting dark. We knew that the small aluminium boat would be straining at the anchor and I could see the face of Sven through his mask and even he looked worried. The boat was not where we had left it. The anchor had shifted but luckily caught on another piece of coral at the edge of the reef. What would we have done had the boat had not been there I have no idea. We were young and so I suppose we were more prone to taking risks.

4. Religions

My parents were not religious so when studying at university I happily took on the logic of evolution. I saw all the fossils in the ground and so to me the proof was overwhelming. Why would anyone believe something else? But for our Buddhist monks above, who grew up with this religion, evolution is the newcomer. It is not their tradition. They understand a different order of things. To change, whole lives would have to be overturned and new lives started. The emotional cost would be too great so it is rare for people heavily indoctrinated in one set of ideas to change to another.

After New Guinea I worked in Tasmania modelling ocean currents for a government organisation (CSIRO). I built a house, continued some more study in evolution, wrote a thesis, and then left in 1998 to wander the world for over 20 years. I funded the trips by living on dividends and share trading on the Australian stock exchange. This could be managed from anywhere in the world so it suited my purpose.

My interest in religion continued but the more I read about religion, the less I believed. When many religions claim that they are the only true one and that, upon death, their members alone will be saved, then you should be suspicious. To fix to any of these religions would be to destine myself to ignorance. My position could only be evolution. I suppose I revered the biological world with its plants and animals. And I suppose this reverence must be spiritual but there was no god or afterlife like the religions.

Just as genes direct the body towards reproduction by reward and punishment, religions do the same by directing a person to accept its doctrine. Heaven or a favourable rebirth is the reward for belief and hell or a lesser rebirth the punishment for disbelief. (Evolution does not punish you for not believing.) Terms like “eternity” and “everlasting” are common in religious texts to entice people to believe. They give hope and hope is attractive. To get the reward, faith in religious doctrine is necessary. I wanted to believe but logic would not allow it. I remembered the university questionnaire where students, at least at that stage of their lives, thought truth was a higher goal than comfort. Religion, with answers for everything, seemed too convenient. I did not want a comfortable religion where the doctrine was decided by others, or a religion unchanged for thousands of years.

For me, religion was not truth. There are too many flaws. A baby who died would surely not remain a baby in heaven for eternity. It would need care and support to grow normally. Who would do this job? A young woman would never be able to have children in heaven and so be denied this valuable experience. Heaven wouldn’t be heaven. For a sportsman, how could sport be possible in heaven? Who would he compete against? Even endless conversation would eventually become dull. With hell, how could a person with no material body suffer pain? Who would keep the fires burning to keep people suffering? Religions brush all these problems aside with “god works in mysterious ways” type of arguments. This is a cover for “we don’t know”.

In everyone there is awe, wonder and curiosity. This was certainly the case for me in New Guinea. It was all new. There was an active volcano a few kilometers away that spewed out smoke and at night sometimes red lava could be seen flowing down its sides. Next to it was an extinct volcano with a lake (Lake Billy Mitchell) at the top. We took the mine helicopter there, jumped out, and cut a landing for the return journey. We planned to camp for a few days. There were three of us and we had brought an inflatable boat for rowing across the lake to measure its width and take its depth. It was about two kilometres across and about 80 meters at its deepest. The year was 1984 and we may have been the first to do this survey. We put the tents up and made the campfire. Usually when you make these types of trips something unusual happens. We collected dead wood from the trees and bushes around and all burned well except the wood from one tree. Despite a large fire, it was still unburnt in the morning. I never found out the name of this species as I am sure this type of wood would have had many uses. The origin of this trip was awe, wonder and curiosity. We were driven to explore. People vary in the strengths of their attributes (as demonstrated by the bell curve). Some are happy to stay at home while others are planning the next trip as they finish the one they are currently on.

How could a religion start? New religious ideas do not have to be true, they only have to be believed. In Freud’s last book, Moses and Monotheism, 1939, he suggests that the first Moses was an Egyptian who lived around the 13th. or 14th. century B.C. The Egyptian pharaoh at the time was Amenhotep IV who rejected the polytheism of the previous pharaohs and adopted monotheism during his reign of seventeen years. He changed his name to Ikharton, left Thebes and built a new capital further down the Nile which he called Akhetaton. Nefertiti was his wife. It was during this period that Moses lived and he embraced this new religion with Aten his god. Not wanting to abandon this new religion and revert to polytheism upon the pharaoh’s death, Moses and his Egyptian followers (Levites) selected the Semitic tribes of Egypt to leave with him and this departure became the Exodus. These various tribes with their new Egyptian religion crossed the Sinai and settled in the Hejaz. Over some hundred years and under a new Moses they lost their Egyptian religion and gained the polytheistic religion of the Midianites of which one of the gods, the volcano god, was called Jahve (John, Jahweh, Jehovah). Jahve recognised the existence of other gods and was jealous of them. But over time the repressed monotheism of the lost Egyptian religion came to the fore and reasserted itself and so Jahve became the only god with all other gods now false Gods. Thus the Jewish religion (and so later Christianity) was originally an Egyptian religion with later added Arabic components. (This book and others can be downloaded from “Snippets” from the menu at the top of this page.)

The Egyptians had the sun god Ra and various lesser gods before Ikharton, then a single god Aten, and then a return to Ra and other gods after Ikharton’s death. None of the Semitic religions are really monotheistic. In Greek mythology, Gods were distinguished from ordinary beings by being immortal. The Devil or Satan of the Semitic religions, whether fallen angel or not, must also be immortal. Were the Devil to die, there would be no one to tempt people into evil. Without Satan, the Semitic religions would not make sense. God and Satan is the duality of good and bad and both are needed to make the religion work. Following Greek tradition (and who wouldn’t), Satan, being immortal, must also be a god, although a bad one. Archangels Like Gabriel and Michael, and other lesser angels, would also be immortal and so also gods.

Genetic evolution has been going for billions of years but our cultural understanding of the process of evolution (the differential survival of offspring) is recent. Darwin mentions many who suggested some sort of progression in organisms, such as Buffon, Malthus, Lamarck and others. New ideas for understanding evolution started as deductions and guesses in people’s minds. Religions objected to the idea that we evolved with the retort “where is the proof”? Ironically, the call for proof was loudest from religious people who gave no proof for their own beliefs. Where is the proof of “god”? I have yet to see a proof. Any description of God such as “he who is all powerful” is simply a tautology.

For some people evolution is a myth. A possible ancestor, the tiktaalik, is thought to have had both lungs and gills. It crawled from the sea to the land and its descendants may have evolved into humans. The whole process was powered by the sun. What a fantastic story. Who would believe it? How embarrassing having such an ancestor! Better to have ancestor that looks like a human (we were made in god’s image). For many people evolution sounds like myth. John Maynard Smith once said that the reason people cannot understand evolution is because they cannot understand time. Going back 4000 years is hard enough, billions of years is too difficult.

Myths are central to any religion. The desire for myth seems inborn or genetic. The recent Harry Potter series of novels has had huge appeal worldwide to children even though they are full of magic and impossible events. Children are most fertile in their imaginations, often telling the most fanciful stories that a parent knows could not possibly be true. For some of these children the novels themselves have almost become their religion. Children want to believe in magic. Adults may look back with fondness (or horror) to the imaginary nursery stories they had as a child.

With very little science, early human populations were like children in their understanding of the world and so we can expect any religions that formed to be embellished with magic. There is romance in myth. There is something attractive about just believing despite the lack of evidence. This all goes back to awe, wonder and curiosity. It is not surprising then that we can still find people trained in science believing that fanciful stories like Genesis are factual accounts of how humans came into existence. Being made in the image of God, Adam and Eve could not have had navels. After eating from the “tree of knowledge” they realised they were naked and covered themselves with fig leaves. Other animals that ate from the same tree do not seem to have had the same problem.

We had an unbearable surveyor working at the mine who was a Christian of the fundamental type, not the sort who kept his ideas to himself. Whatever logic you used fell on deaf ears and he just waited for you to stop and then continued with his dogma. He thought that everyone had to have the same ideas as he had. He wanted to save people and was worried about their souls. He thought the soul immaterial. For most religions, upon death, the soul is meant to go to a heaven or transmigrate to another newborn human or some other animal. I suppose when similar characteristics of parents and grandparents are noticed being passed on down the generations, it is only natural to assume that there is some sort of vehicle for this transmission. Seeing genes as an explanation was not possible before modern chemistry so the immaterial “soul” became the agreed explanation.

There are a number of problems with this idea. As the Earth was originally a fiery ball with no life before it cooled, souls must have come later (unless they were lying in wait somewhere for the geological processes to complete). When souls did come, did they start with Homo sapiens? What about other species such as Homo habilis and Homo erectus, did they have souls? And if so, what about even earlier ancestors all the way back to fish and beyond? Where is the boundary on the evolutionary tree between having a soul and not having a soul? Could there be a situation where a parent does not have a soul and a child does?

Another problem is our population explosion. New souls would need to be created by some means unknown at a fantastic rate. Similarly, if there were a catastrophe with an ice age or asteroid strike and the population plummeted, where would the excess souls go? Is there a temporary repository apart from heaven or hell where the souls could reside?

Could only Homo sapiens have souls as suggested by Pope John Paul? It is generally agreed that Homo sapiens split off from previous species about three hundred thousand years ago. There is some evidence of figurines and burials around thirty thousand years ago and if this was the start of religions they could not have been very sophisticated. But let’s say we have been religious for about ten percent of our existence. Did the Homo sapiens for the first ninety percent have souls? Can you have a soul without being religious?

For me, the idea of souls does not seem very compatible with the idea of evolution. With all these mythical ideas, the deeper you look the more far-fetched they become. It is easy to think of better explanations for the soul. In the mind are chemicals including the inherited genes in the nuclei of brain cells. As well, cultural ideas we learn are absorbed into the brain. All these genetic and cultural ideas make up a “pattern” of chemicals that is more than the chemicals themselves. It could be that this chemical pattern is the soul. Learning involves changing this pattern. In this sense then, these patterns are made from materials and therefore are material yet in another sense the patterns are more than the material itself and are therefore immaterial. On this basis, I have no problem if someone says the soul is immaterial. For evidence, say a person suffers a car accident. A serious knock can cause concussion and so damage to the brain. The pattern of chemicals in the brain has changed and friends may see the person as having a different personality. This change of character also happens to some people as they age and the brain decays due to conditions such as dementia. To some extent, these genetic and cultural patterns are passed down the generations through genetic reproduction and the cultural teaching of children.

Another religious idea is “original sin”. Jealousy, greed, hate, and so on, are all genetic attributes that we inherit in varying strengths (again, according to the bell curve). They are normal attributes that allow our survival in the evolutionary struggle for existence. They are why nature is “red in tooth and claw”. Religions, not knowing genetics but wanting to label these attributes, chose “original sin” as a phrase as good as any. Both “original sin” and “soul” are early metaphors coined at a time when biology and chemistry were poorly understood.

Religions have evolved to fit the genetic properties of humans. Cultural ideas address genetic ideas. I am sure the cheering pleasure of music, including singing and chanting, came before religion. Religions have included this in their doctrine. Having a church service followed by hymns, with all the people singing together, is a unifying and pleasant experience. Some of the most beautiful music written has been religious music. Religions also include the feeling of being in a large space. Churches are caves above ground and they can have a grand feeling. They are dry and safe, both genetically desirable states. They can be a place to get away from the chaos of life and to reflect and meditate. Their size, and possible echo, creates awe for impressionable children.

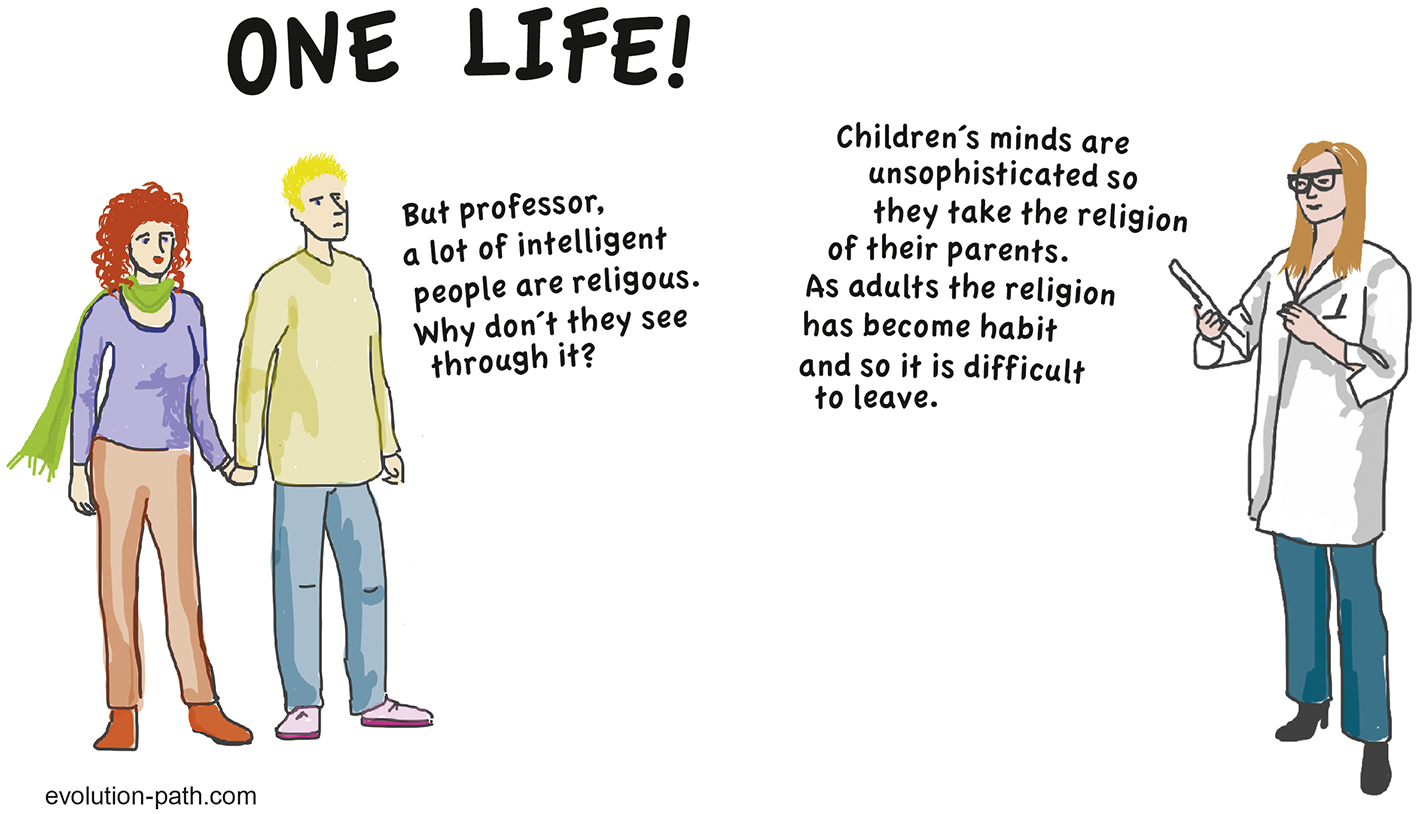

Also included is socialisation. Children fear being different from the people around them and so fear social isolation. Having different cultural ideas from other children reduces happiness. Fear of isolation pushes children into religion. Later, fear of isolation stops adults from leaving.

Religions address genetic loneliness by making religious figures, such as Jesus, saints, Krishna or other deities, best friends. Small shrines in streets and caves or statues and paintings kept in houses, all give a sense of belonging. These deities can become part a family’s social life through prayer and offerings. Requests for certain outcomes can be made. If a request is answered it is a “miracle”. With these figures as best friends, people reduce their loneliness. These new friends can bring great comfort with a feeling of being loved and protected.

All religions I know of have been started by males and so it is only natural that the doctrines produced will be centred around the thoughts and activities of men. With this bias men are often given higher status and greater rights in religious scripts. Most religions put men firmly at the head of the family. The education of boys usually takes precedence over that of girls. Women are usually barred from religious office or, if not, given unimportant roles. Some religions allow men more than one wife but few allow women more than one husband. All these non-symmetries make it clear that religion is a male phenomenon. They have been invented by men for men.

Religions are not the only organisations to have evolved by offering explanation, comfort, hope, and protection. Pseudo-religious organisations like the Masons offer fellowship with strong bonds often forming among members. Other groups, such as the Lions and Apex, do charity work for non-members.

5. Evolution

Ok, I believe in evolution. Would I have been happier if I had adopted one of the established religions? Probably. I like the idea of living forever. I like the idea of escaping the unknown. If we believe in god, who knows everything even if we don’t, then there is no unknown. But I would rather have truth than comfort. Unfortunately, religions contain unrealistic beliefs that involve too many compromises. They are fantasies to be indulged in. In some cases, people are forced into these fantasies with no chance of escape. But overall, I think evolution is the more difficult path to follow. Another common trend today that appears to be growing is just to live, without taking any interest in religion or evolution.

In many countries, the parts of science that expose the myth of religion are avoided in schools. Explanations like the Big Bang are against the idea that god created the world. The idea that life evolved by chance from chemicals in some “primordial soup” is demeaning to some people and so avoided. Escaping means looking the other way at unpleasant truths. In contrast, other biological ideas such as those of medicine are readily accepted and are taught in all the universities. Scientific ideas, such as those that allow aeroplanes to fly and mobile phones to communicate, are embraced with enthusiasm and are in constant use. So it seems that religions agree with those parts of science that are not a threat to their dogma, but reject those parts of science that expose and challenge them.

Evolution is still a minority position because many people have not really been exposed to it. Education levels are poor in many countries with children receiving only a few years of schooling before having to work. As they grow up in a religious setting they naturally continue the ideas that they have been taught.

Some religions are not so much to make us happy in this lifetime, but to make us worthy of a happier life in the next. Work must be done to obtain this future happier life. This includes attending a place of worship and giving money for the religion’s upkeep. People may pray and possibly make offerings. Time and effort is required to practise a religion. Some may consider that a monk, who spends his life in prayer and penance in the expectation of greater merit in an afterlife, has wasted his life. In this sense a religion can be seen as a burden. But for the evolutionist this burden is no longer necessary. One does not have to perform in this lifetime in order to earn a reward in the next. The evolutionist can use this time in other ways.

Rishikesh is a small town in India high up on the Ganges, India’s holiest river. Just south of the town was the ashram of the Maharishi Mahesh Yogi (see “Travel Stories” in the menu above) who was made famous when the Beatles stayed there. The upper part, Laxman Jhula, straddles the river and is joined by a footbridge. On the east side, over the bridge, are a series of ashrams offering meditation courses run by dubious gurus. Overlooking the bridge is a coffee shop frequented by westerners and where you could meet the people doing courses with the gurus. Some wore lockets around their necks in which were the various gurus’ pictures. These people had come on spiritual discovery tours in search of new ideas. They were escaping the western world. I had many great conversations there.

Exercises given by a guru may include stopping the random thoughts that continually enter the mind by concentrating on breathing or some object. These exercises are designed to repress the expression of genetic and cultural ideas. When control of the mind is gained it can be redirected. While we might recognise deficiencies in our lifestyle we are reluctant to change and jump into the unknown. We have developed habits that are hard to break. We fear change. The Guru’s first task is to use meditation to take you to a place you have not been before. The Guru guides you in your jump into the unknown. By stopping the expression of some ideas, habit can be broken. Other methods to assist in breaking existing habits can include different clothes, a new name, new friends, new foods and new routines (such as waking at five in the morning).

If all cultural ideas are pushed out of the mind temporarily (during meditation) so as to make it empty, a person cannot be unhappy. There are no active ideas left to cause unhappiness. There is no longer a self to experience unhappiness. A person has only the genetic part left. Such unusual states produce entirely new mental states that seem fantastic to the novice. People are surprised. Unfortunately, the Guru may link these new meditative states with the supposed truth of his accompanying dogma. Experiencing new states does not mean that there are seven transcendent states leading to Nirvana. New states do not prove the transmigration of souls. These different states from meditation are natural properties of the body that can be produced without any reference to spiritualism or religion. An increase in happiness of the student does not necessarily imply that the Guru should receive a large financial donation. The Guru’s methods are not new but variations of general themes already existing in Indian philosophy.

But we can learn from this method? By abandoning more and more cultural ideas you move back further and further to the genetic self. Expressions such as “discover the child in you” recognise this cultural idea-shedding process. Children, particularly very young children, are minimally influenced by cultural ideas. They have not yet had time to take on an intricate set of ideas. They have not yet learned guilt. They can laugh endlessly at the most simple things. Their happiness is from the heart, that is, their happiness comes from the genes. Generally this method works. For a person seeking an increase in happiness, by reducing cultural ideas, and hopefully the ones causing unhappiness, happiness has a high probability of increasing. Ideas like language or how to drive a car obviously do not need to be reduced. But other ideas such as the number of artifacts one needs, appearance, pride, ambition, and status, could all be candidates for reduction or change.

Change can be difficult. Parents may impose a religion on you without choice. They may push you into a profession in which you have no interest. Poverty, caste or gender might stop you from getting the education you want. You might fall in love with a person of the wrong religion. Many people with genetic ideas pointing in one direction can be pushed by circumstance into a different direction. As a person’s original genetic ideas will be poorly addressed by this new direction, happiness will suffer.

To make changes, finding out the strengths and weaknesses of your inherited genetic ideas is the key. Know yourself. Genes are real and part of us and we should make the most of them. Many genetic ideas are to be celebrated not denied. Other ideas, such as those for jealousy or cruelty, may need to be repressed. Correctly utilising your genetic inheritance is the elixir of life. After discovering these genetic ideas the next step is to find those cultural ideas that best address them.

New ideas can have a huge effect on your happiness. Say you find out that you have won the lottery, landed the job you always wanted, or you are going to be a parent, then happiness might overcome you. For the next few moments your mind is swimming in pleasant thoughts. Can you get the same pleasant thoughts without the external piece of exciting news? Can you generate them from within? If so, then you have solved the riddle of life.

6. One Life

Evolutionists can only see themselves as evolved animals. There should also be compassion for non-human animals.

We should recognise the possibility that much about the Universe may never be understood. The evolutionist is able to say “I don’t know”.

The evolutionist should reject selfish actions that are detrimental to societies and the environment.

The evolutionist will have a spiritual relationship (awe, wonder and curiosity) with the current world and reject the magic of religions.

There is only one life so evolutionists should look to their genes and find those cultural ideas that best address them.