Snippets

A Collection of Short Stories from Books of the Past

I have always enjoyed books that illustrate events of some one or two hundred years ago. They are a window into the past. I found many of these books, unloved, in the dusty second hand bookshops of Adelaide. But many of these early books deserve to be loved as they were written by adventurers who chose an unknown path in life. They were prepared to take risks. Others were missionaries who took the moral high ground and often left destruction behind them (see the story by Arthur Grimble below). I prefer books by people who travel to give rather than take; the explorer or scientist who tells life as he sees it or the free-spirited traveler who desires adventure. Often these genuine travelers came to love the country and people in which they travelled and never returned to their country of origin.

From these books I present some “snippets” that could be thought of as short stories. Many great adventures have never been told but some authors have written their experiences down. These early travel books are now becoming forgotten. By reading these snippets some may wish to follow up the books they find interesting. Many of the older books can be obtained in .pdf form through Archive.org as their copyright has expired (older than 70 years). Some of the books can be downloaded from this site.

This project of “Snippets” is just beginning and over time, I hope to extract many more interesting stories and include them here so this e-book will expand.

Below, text added by me will be in italics while text from the books will be in normal script.

************************

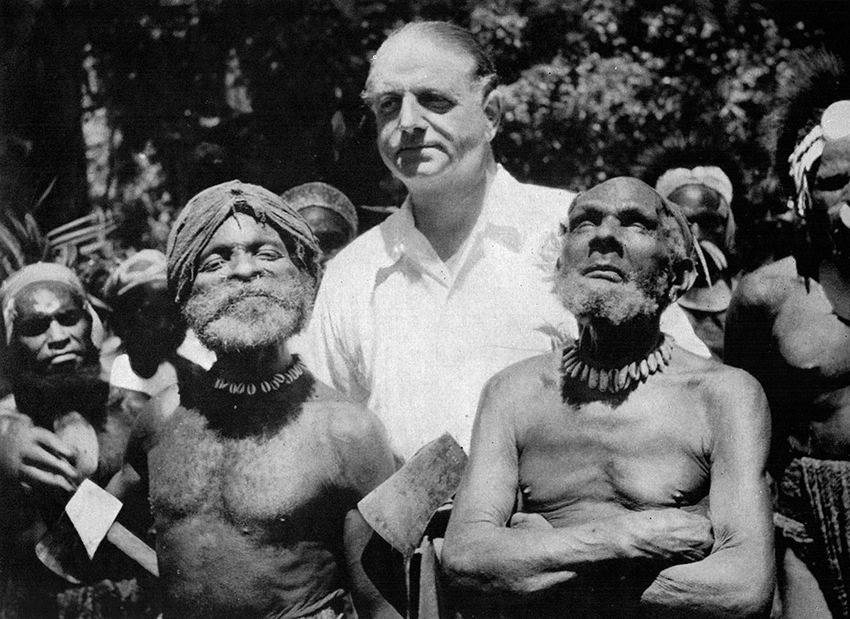

Alfred Vogel, returning to Sweden after living amongst the pygmies of New Guinea, finished his book of travels with the following paragraph:

Sometime later, on an evening of high summer, I stepped into the plane that was to take me home, and five days later out of a Dutch plane from Copenhagen into a snowstorm at Stockholm. The following day, standing at the junction of two busy streets, I found myself wondering why people were in such a hurry and why everybody looked so grave and relentless as they rushed along or struggled in queues. What are the profits to be had from this hustle after what are largely fictitious values? Once some native porters who had sat down to rest said to the white man who wanted to drive them on: “We are out-distancing our souls, and now we must wait so that they may catch us up.” After that journey to the great island of savages and birds of paradise I have more and more come to the conclusion that in the art of living the savages are often our superiors. They live according to Nature’s wise rhythm, and in conformity with the laws of creation, which we are eagerly trying to abolish, they dispose of their four problems of eating, loving, sleeping, and hunting without unnecessary bother and fuss and bustle. (1953, p. 159).

***************************************

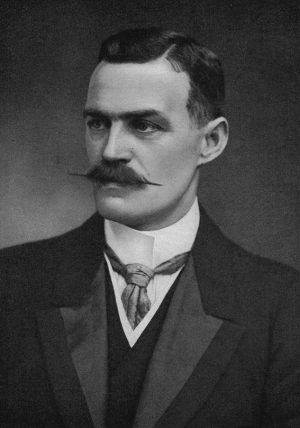

Captain Monckton was born in New Zealand in 1873 and at the age of 23 went to New Guinea seeking adventure. He tried gold mining and pearl diving and eventually became a Resident Magistrate of various districts.

On the same boat trip when I made the acquaintance of the swordfish with the worm in its head, I also fell in with a most extraordinary fishing rat. We had landed and camped for the night upon a small coral island surrounded by submerged coral boulders and, but for a few stunted trees, bare of all vegetation. Shortly after dark I was disturbed by rats crawling over me and at last in disgust went and slept in the whale boat. In the morning I landed again and, while my boys were preparing breakfast, walked to the other side of the island; then sitting down I began my ante-breakfast pipe, whilst I pondered on what on earth the rats on the island could find to live upon, as food there was apparently none. While sitting quietly there, I noticed some rats going down to the edge of reef —lank, hungry-looking brutes they were, with pink naked tails. I stopped on the point of throwing lumps of coral at them, out of curiosity to see what the vermin meant to do at the sea. Rat after rat picked a flattish lump of coral, squatted on the edge and dangled his tail in the water; suddenly one rat gave a violent leap of about a yard, and as he landed, I saw a crab clinging to his tail. Turning round, the rat grabbed the crab and devoured it, and then returned to his stone; the while the other rats were repeating the same performance. What on earth those rats did for fresh water, though, I don’t know, as there was none on the island I could see. (1920, p. 81–82).

The mission station is built on the island of Dobu, an extinct volcano; the only evidence of volcanic action at this time being a hot spring bubbling up into the sea, over which small vessels used to anchor, to allow the hot water to boil the barnacles and weeds off their bottoms (1920, p. 85).

At the Woodlark Island gold-field, at the time, a very peculiar position existed. The Mining Act, under which I worked, was an Act adopted from Queensland, where all lands not alienated were vested in the Crown; certificates of titles, rights or leases in Queensland being granted upon that assumption. In New Guinea, however, under our constitution, all lands not purchased by Government, not gazetted as waste and vacant, were held to belong to the natives; no land in Woodlark had been purchased by the Crown, nor had any been taken over as waste or vacant. The position therefore was, that on behalf of the Crown, I was granting titles to land to which the Crown itself held no title. As a matter of fact, I believe that if the natives had sufficient knowledge, they could have capsized the title held by every miner and mining company in Woodlark, and could have entered into possession of all the claims or mines; moreover, they could do so still, unless those lands have subsequently been acquired by the Crown (1920, p. 263–4).

Giwi then told a tale. I have related in my previous book how he had built a fleet of light canoes and held the coast. Giwi said that he had gone out to fish on the reef; the fishing was good, and no one bothered to keep a lookout, for like Admiral Blake of old he commanded the seas, and knew that he could outpace, and outfight any one venturing near his canoes. Suddenly one of his men gave a yell of horror, and looking around he saw about a mile distant and enormous white devil canoe (steamer), pouring out volumes of black smoke, and coming against wind and tide! Giwi collected his canoes; he looked at the appalling devil canoe; he did not know whether to fight or fly; then suddenly his men yelled, “the men in that devil canoe are white!” Flesh and blood could not stand that! Whoever heard of a white man!

“Scatter and fly over the reef!” was old Giwi’s order; “the thing of death is upon us.” The canoes reached the shore. “Marry off all the virgins at once, without payment to the fathers; kill all the pigs, and hold a great feast, for tomorrow we die. The thing of death has come,” ordered old Giwi as he landed. Giwi’s orders were obeyed; but in the morning there was no sign of “the thing of death”. And according to his statement, his talents as a diplomatist were strained in settling the affairs of the married daughters and the slaughtered pigs! Toku permitted himself a remark:

“My father was always hasty; he always hit us before he said anything.”

“Oia,” I remarked severely, “clump Toku’s head”

Toku’s head was clumped, the while my tea party smiled approval, and Giwi passed up his cup for more tea. (1922 p. 59–60).

Download Monckton “Experiences” in Pdf.

Download Monckton “Last Days” in Pdf.

************************************************

Cecil Thomas Madigan was a lecturer in geology at Adelaide University for twenty two years and travelled often to central Australia on exploratory trips. He had an interest in deserts and was the first to cross the Simpson Desert and named it after Mr. A. A. Simpson who was the president of the Geographical Society of Adelaide. This adventure was achieved with camels. He also went with Mawson to the Antarctica as the group’s meteorologist.

The returning boomerang is a thin little thing, actually a toy, known only to a few tribes in the south. To make it return, the thrower must have a fresh breeze on his left hand. The hunting or fighting boomerang is quite a different thing, much heavier and stronger, with no returning properties. You will not find a boomerang among all the wild tribes of to-day. They have never heard of it. The mission blacks of the south are taught to make them for tourists. I have followed up the boomerang question and collected many boomerangs, but the only returning ones I have come from the Point McLeay Mission Station on the lower Murray, and from Ooldea on the east-west railway where they are being sold to the passengers. They are a fascinating toy, but the limitations of direction and manner of throwing make their returning properties of no practical value.

A friend of mine once said he was sure he had a good returning boomerang and asked me to test it, so we went outside and threw it in the approved manner. It travelled extraordinarily well, and was last seen passing over the roofs of some houses on the far side of a vacant block of land; we never saw it again and decided it was not of the returning kind. (1946, p. 28).

*********************

Arthur Grimble was a Colonial British administrator in the Gilbert Islands, near Papua New Guinea. He wrote two books: A Pattern of Islands and Return to the Islands.

Monogamy was forced on the Gilbertese by British law at the turn of the century, when Protestant missions had been at work in the islands for about fifty years, and the local administration for a decade or less. There was no popular demand for it. On the contrary, except in one or two southern islands, tremendous pagan majorities still clung to the polygamy of their ancestors and the strictly controlled system of sex conduct that went with it. But nobody spoke for the pagans; the petition of the sectarian minority went through to London backed by the administration (so much must be said in fairness to the Colonial Office of the day), and that was abysmally that.

As soon as the new law came into local force, a multiple of women who had enjoyed the honourable status of secondary wives under the old system found themselves considered potential adulteresses. That is to say, the criminal code of the day allowed for no distinction between the situation of a sub-wife and that of any ordinary breaker-up of homes: she could be brought to trial before her island court and imprisoned for common adultery if anything so contumacious as pagan love or loyalty tempted her to still cling to the father of her children. By the same token, the rising Christian generation was taught from the village pulpits to call her children bastards, and did so, freely.

The pagans liked and admired the white man: not even this treachery could shake their incredible loyalty to him; so there was no attempt anywhere to rebel against the law. Only, after lifelong partnerships, hundreds of secondary wives were put away in shame by their men, while as many women, whose mates would have held them despite everything, returned to their villages rather than stay as and be placarded as harlots. There were many suicides amongst the middle-aged.

A quarter of a century after this event, I talked with a pagan friend of Tabiteuea whose mother had preferred death by her own hand to living on, either in unlawful concubinage with his father or in desolation without him. Though she was only a sub-wife, she happened to love both her man and his ceremonial bride, her older sister.

So she said one evening to her son, who must have been about twenty at the time, “Your father will be happy with my sister, and she will always be good to you for my sake. As for me, I shall be better out of the way, since the law has made a shameful woman of me. I go now. Tell them I died loving them”.

The boy took her words for nothing but a cry of grief more bitter than usual. He put her arms round her, saying, “Neiko [Woman], we shall have each other. I will go and live with you in your father’s village.

She smiled at him: “You are a good son,” she said, returning his embrace. “Stay here and be a joy to your father.” Then she walked out into the bush and hanged herself.

The next day, his father and aunt hanged themselves to the same tree. (1957, p. 98-99).

***************************************

Eric Muspratt at one stage grew pineapples in Queensland, before taking up an offer to manage a coconut plantation in the Solomon Islands.

By some accident or ignorance a boy broke his tambu. The Vaili man discovered the breach and issued a spiritual condemnation. The boy’s movements were stealthily watched by night and when he left the village clearing alone or entered one of the narrow jungle pathways a Vaili man waited for him in the darkness of the jungle. The priest held a short stick with a fish bladder made luminous by phosphorus and when the condemned boy approached this was suddenly uncovered and held before his face. From the moment the boy set eyes on this shining bladder he was doomed to die. For he believed that it was the spirit of an ancestor come to summon him to the spirit world.

Sometimes they dropped dead on the spot, while the stronger, or perhaps less believing, ones lingered for a few hours or days. But they never failed to die. (1937, p.79).

(This death by fright is not an uncommon event and is the principle behind voodoo and other magical systems. Scientific research shows that the brain, via the vagus nerve, slows and eventually stops the heart when hope for survival is taken away. For details, see Denton (1993, p. 71-74).)

************************************

Missionaries went to Africa to spread the word of God with varying success. Africans already had their traditions, their idols and their religions and the main goal of the missionary was to substantially replace these with the Christian religion. Which was better is debatable, but on some occasions they did great good. The following story comes from John Weeks who lived in the Congo for more than thirty years.

One evening I heard a terrible amount of shouting and screaming, and on going to the scene of the excitement I found two women strongly bound who were weeping most bitterly, and begging to be set free. I asked them the reason for being thus tied, and they replied, “You know our husband, Mangwele, is dead. He is to be buried to-morrow morning, and we are to be buried alive with his body. Untie us, white man, and save us from such a death.”

I knew the custom of the district very well, but have never been brought into contact so closely with it. In every family of importance there were one or two women called mwila ndaku, which meant that when their husband died they were to be buried alive with his corpse, unless in the meantime they bore children, when other women took their place. Every time they heard their name it was a reminder of the awful fate that awaited them.

From my heart I pitied the women, and turning to the members of the family I pleaded and remonstrated with them in such a way, and with such God-given eloquence, that at last they said, “All right, white man, we will give up this custom,” They untied the women, who at once began to dance about us, relieved that they had been rescued from such a horrible fate.

Next morning the men came and asked me to attend the funeral, to see for myself that they really intended to keep their promise. I went, and for the first time in the history of the district a man was buried without living women being inhumed with the corpse.” (1913, p. 103–104).

***************************************

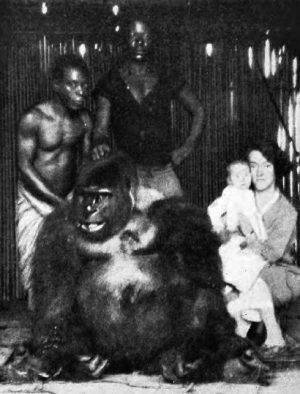

Fred Merfield was apprenticed to drapers but wishing to escape the boredom, he answered an advertisement for an assistant on a plantation in German West Africa, and being the only applicant who had a little German that he had learnt at school, was chosen for the position. He became a reluctant hunter and collector of animals for the museums of Europe. A one stage he kept a black-faced chimpanzee who smoked twenty cigarettes a day and in the evening drank red wine with an aperitif.

Disease:

One of the worst pests of tropical Africa are the tiny fleas called jiggers, which burrow unnoticed under the skin of one’s toes and set up an irritation and infection. Native children are often permanently crippled by these parasites, and at the end of each day it is always a precaution to have one’s feet examined. The usual way of getting them out is with a fine splinter of bamboo, and this can be a painful operation unless preformed by an expert. Bo-Bo was as good as anyone I knew. You had to sit down beside her, present your feet and a piece of bamboo, and leave the rest to her. With your toes just in front, so that she had to squint, she would wriggle the beastly things out in no time, and she was so skilful at it that natives would queue up for her attention. Dr. Bo-Bo’s evening surgery was a sight to be remembered. (1957, p. 69–70). (Here Dr Bo-Bo was a chimpanzee; we cannot assume that every doctor is a human).

Sexual relations:

Polygamy is general. Besalla had four wives and the chief Oballa had six. Girls are considered nubile when they are between twelve and fourteen, and for the most part they get on well with their fellow wives. Each spends two consecutive nights with her husband, though the senior wife, who has authority over the others, may spend longer. The woman thus honoured also has to cook for her husband during the period she is with him and supply the food from her own plantation, so that the more wives a man has, the less work they have to do. Intercourse is forbidden during pregnancy and during the two-year suckling period, and if this law is broken it is believed that the child will die. On the death of a man his women are inherited, along with his other property, by his sons, who may marry or sell them again. The woman is thus always some man’s property, and may be sold or re-sold two or three times. It would never occur to these women that they could lead any other kind of life, and they are as happy as women anywhere else. If their owner-husband happens to be old or frigid they soon find more vigorous lovers elsewhere, usually with the husband’s consent.

I once asked Besalla why he needed more than one wife. “Man no want chop (eat) Jamba Jamba every day,” he chuckled. Jamba Jamba is a kind of spinach which upsets your stomach if eaten too often.

Boys are circumcised at puberty, usually in June, but there is no special ceremony. The operation is performed without and anaesthetic by the village witch doctor, using a sharp iron knife, and watched with great interest by the young girls. A boy who cries out or shows any sign of pain is teased for weeks afterwards and has great difficulty finding a wife. As soon as possible the boy is given over for instruction in love-making to his father’s eldest wife, usually a woman past child-bearing, and remains with her until he is old enough to buy a wife of his own. (This, I had learned before, was a custom practised by several tribes in the Cameroons.) The Mendjim men file their teeth to points, without any ill effect, yet if a European breaks a tooth or even cracks the enamel, decay very soon sets in. (1957, p. 202–203).

Warfare:

“When I was a young man I was a great warrior, and my father was the chief of this village. One day we went through the forest to Toukou in the Kaka country and then on to Bimba, which we burnt to the ground after swimming across the Doume river. The Kakas heard us coming and ran away, but we killed many of their men and captured many girls, whom we brought back here and sold. We brought back the boys too and kept them as slaves. We ate the men we killed, taking out first the stomach, liver and heart, which are of course the best parts of man or animal. We brought other Kaka men back here alive and gave them to our fathers, who killed them for food. Our fathers tied up these men and killed them by carefully cutting their throats, so that the blood could be drained off and drunk. We also killed and ate some of the women. Everyone tried to get the sexual organs, which are the nicest parts, being full of fat.”

“Our chief, my father, commanded us when we went into battle, and he wore a plume of red parrot feathers on his head. We the Mendjims were the strongest tribe, for we had guns. Only the N’Jem people had guns beside ourselves. I do not know where they came from, but they were all bush guns (flint-locks) not nice guns like yours, and we bought them with ivory. Sometimes our young men went away for months and brought these guns with them. When I was very young, another tribe called the Gart used to make war on us. They came from the west (the Akonalinga side) and they too had guns. They were always taking our away our men and women. They joined up with the Kakas and used them as guides, but we beat them all at last. We hate the Kakas even today.” (1957, p. 205–206).

Hunting:

I do not like to get sentimental about animals, but I must confess that I fell for that pair of gorillas as soon as I set eyes on them. They had both just reached maturity and were obviously in the first year of their life together. The female was pregnant, with about a month to go, and was scarcely half the size of her gigantic lover. Every morning they came out of the bush at about seven o’clock, sat down in the plantation and began to break all the sugar-cane within reach. Usually they only took a bite or two from each cane before discarding it for another, so that, as usual, they ruined far more food than they could eat.

One day one of Besalla’s wives, ignoring her husband’s instructions not to visit the plantations while I was there, put in an appearance and was seen by the gorillas. The female at once made for the bush, but the bull stood erect and beat on the top on his vast belly, where upon the woman hastily retreated and the bull sat down again to resume his interrupted meal.

Within a week the gorillas had destroyed half the plantation. Besalla was furious, pointing out, quite rightly, that money could not replace his lost food. He insisted that I should shoot them, and threatened to kill them himself if I did not. If my gorillas had to die I preferred to shoot them, for the spears and poisoned arrows of Besalla would have given them a slow and cruel death, so the next time I went to the hide I took my rifle with me. Strangely enough, they did not appear that morning, and when Besalla heard this he at once decided that they must be ju-ju gorillas. They had known by magic, he said, that I would have my gun with me, and had kept away. Moreover, there was no doubt that they were destroying his plantation in revenge for the gorillas he had killed.

I prevailed upon him to give me another chance, and the next morning he came with me to the hide. This time the gorillas turned up as usual but when I looked along the sites of my Mannlicher I could not bring myself to kill them. Instead I fired three times above their heads, and I was delighted to see the pair of them rush back into the forest. But Besulla’s anger had now turned to fear; he refused to believe that I had fired without intending to kill, and was convinced the ju-ju gorillas had warded off my bullets by magic.

That evening there was a big palaver in the village, and the witch doctor worked furiously preparing all kinds of charms and ju-jus against the gorillas. I hoped they would not raid the plantations again, after the scare I had given them, but they turned up on the other side of the village two days later. Armed with the charms and ju-jus, as well as with spears and cross-bows, Besella took his men off to track them down, leaving me disconsolate and unhappy in the village. In the evening they brought back the body of the female. My diagnosis of her condition was correct, and I bought and preserved the almost fully developed foetus, which I sent to the University College, London. The young bull, however, had escaped the hunters, and so far as I know he never again appeared in Arteck. (1957, p. 207–208).

Habits:

“Then she called over one of the youngest girls and showed Hilda a most peculiar custom which is, as far as I know, confined to women of the Kaka tribe. The girl produced from her mouth half a dozen small stones, weighing about two ounces altogether. All Kaka women carry such stones under their tongues, even when they are eating or asleep, though I cannot imagine why they are never accidentally swallowed.

The stones are usually small pieces of quartz and are called Telembe by the Kaka people. Girls begin carrying them when they reach the age of seven and they are sometimes exchanged as a sign of friendship. The number varies considerably; I once found a girl who kept thirteen of them under her tongue. A dying woman will distribute her stones among her daughters, so that they are handed down from generation to generation. Every girl knows her own Telembe stones. I have several times taken them from a dozen girls and mixed them up, but their owners were always able to identify them. They have no apparent function, and no one knows, least of all the Kakas themselves, how the custom originated or why it is maintained. (1957, p. 228).

Misunderstanding:

“Fred,” said Hilda one morning, “You know those little baby dolls we were given as wedding presents in Germany, the ones we keep on the shelf?” Why are the villagers always staring through the door at them?”

I really had no idea myself and I called over two or three of the men and questioned them. After a great deal of discussion it emerged that the dolls had fascinated them from the time we had arrived. They had seen me preserved the unborn babies of gorillas and chimpanzees and they imagined that the dolls were my offspring pickled in the same way! Nothing would convince them otherwise until I let them handle the dolls and feel the texture of the celluloid they were made of. (1957, p. 258).

***************************************

John Taylor was an Irishman who travelled to Africa and eventually became a hunter of elephants, selling their ivory to make a living. This event happened in Mozambique about 1925:

We had heard the drums beating in another kraal in a slightly different direction and immediately started out. We had only a mile and a half to go and long before we got there we could hear the terror-stricken yells and screams of the unfortunate people. Things were in a bad way here. There seemed to be lion everywhere. There was one up on the roof immediately in front of me trying to tear its way in through the thatch. I shot it, and it tumbled to the ground with a snarling roar. But I was confident of my shot and anyway could not attend to it just then even if it did require another bullet. Two more of the brutes emerged from a hut right beside me when they heard the shot. They were only nine or ten paces away. I killed both of them also without any trouble. (As I later found, they had broken down the reed door and killed all the occupants of the hut: an old grey haired woman and three little children.)

But that was not all. Such appalling screams had been coming from another hut on the far side of the kraal, that I was convinced that another tragedy must have taken place there. The yelling and screaming everywhere had ceased as soon as I fired the first shot; but over there it had seemed to continue for just a moment longer and there had been an unpleasant choking sound immediately before it stopped. I made my way over there, swinging the beam of my lamp on each and every door and roof. At last I saw what I have feared: a broken down door and a gaping hole in the thatch of the roof.

Naturally assuming that the killers would have departed I walked straight towards the open doorway to see if there was any life left amongst the occupants. But, as a matter of course, I was carrying my rifle ready for immediate use as I stopped to enter the hut. And it was a good thing I was; because whilst I was still stooping and only halfway into the hut, peering around the reed door which had been pushed to one side but had only half fallen, I found myself face-to-face with a big lioness with another as big beside her and, immediately beyond them, a magnificent black-maned lion. The nearest of them was a mere five feet away. The interior of the hut was like a slaughter house. There were five dead girls and the lion were busy feeding on them, the hard mud floor a sea of blood.

I could not take all this in immediately. I realised that the maneaters had killed and saw that huge pool of fresh blood. I had to make up my mind without delay just what I was going to do. Had we been outside in the open it would have been perfectly straightforward and had there been only one, or at most two, of them in the hut it would not have needed much thought; but I had never tackled three of the brutes before under such conditions. I knew I could kill two—but what was the third one going to do? I knew that animals will seldom attack something they cannot see, and, of course, these would be completely dazzled by my lamp. All the same that third one would know it was trapped there in the hut and might well make some sort of attempt to break out, and then, even as I opened fire, I remembered that big hole in the roof: at least one of them must have broken through it and so I could only hope that if any of them tried a break when I commenced shooting, they would try it in that way and not out of the door and past me. There wasn’t much room for a lion to get past me, and I had no hankering to be brushed out of the way by a lion.

It is really remarkable how long it takes to describe one’s thoughts during such tense moments—thoughts that whip through one’s mind quite literally at the speed of light.

The nearer lioness stood up as I stuck my head in, but her two companions continued to lie on the bodies of the slain. Accordingly, I killed her with my first shot: at a range of about five feet there could be no question of missing. At the shot I saw out of the corner of my eye, black-mane leap for the hole in the roof. I could do nothing about it. The second lioness had jumped to her feet, but since she had been looking towards me did not know that the big fellow had made his break. I had no difficulty killing her as she merely stood there gazing at the light and then down at her sister, doubtless wondering why she was taking no interest the goings-on.

I regretted losing the big black-maned leader of this pride as I stood there looking at those five dead girls. The eldest of them might have been sixteen or seventeen years of age. Even so horrible a death could not disguise her beauty—she was an exquisite creature by any standard: her features, her eyes, lovely young breasts that required no artificial aids.

But black-mane was gone. I followed the direction in which he must have fled—as my gunbearer, who was immediately outside the hut whilst all this had been going on, would have otherwise have seen him. And it was very fortunate that he had broken in through the roof other than immediately above the door, otherwise he would have come straight down onto my man’s head. Still, that would have meant that he would have had to jump right over me and my light, which was not very probable.

The wretched villagers’ delight at the slaying of five of the man-eaters was badly offset by the deaths of so many of their own members. And on top of that there was the further certainty that the black-maned leader of the pride could be none other than the wizard himself. Otherwise, how explain his escape when he was actually in the hut with the rifle which had just killed his two wives and three of his companions? It could only be a were-lion. And then inevitably someone remembered that last time, the big-maned leader of a pride had never been shot. It goes without saying that when the news of this got around the district every witch-doctor and wizard confirmed the general belief. It was useless my attempting to assure them that black-mane was just another lion that would fall to my rifle if he continued maneating. What does a white man know about such matters? They were much too well-bred and polite to say so to me, of course; but I know the African and know that dead-pan expressionless look of which he is such a master when he drops that curtain back of his eyes. The white man is without doubt, very clever with his guns, his cars, his airplanes and such; but what does he know about witchcraft? (1959, p. 154–157).

Elephants, although vegetarian and therefore not seeing the human as food, can also lose their fear of humans and become violent. We always suppose that it is the human who stalks and kills elephants, but in the following case the roles are reversed. Here an elephant hunts humans.

I arrived at the local chief’s village, which was roughly in the centre of the area that was being disturbed by the raider. The chief told me that the brute was much worse now than he had been. Some pseudo hunter who had been passing through had shot at and wounded him but had not bothered to follow him up and finish him. The hunter’s excuse was that he was in a hurry, but the chief and the local natives knew that the real reason was that the man did not like walking and was much too scared to follow up any wounded and potentially dangerous beast, much less one with so bad a reputation as this bull. Once again the deaths of several innocent natives could be chalked up against a nervous and inexperienced “sportsman”: a man who thought nothing of wounding an animal and then going his way uncaring; but a man who would like all his friends and acquaintances to class him as a big-game hunter. I have met all too many of them.

The direct result of his wounding this bull was to turn him into a man-killing rouge. The elephant liked to wait close to some path much frequented by natives and then, when unsuspecting travellers passed by, he would charge out without warning, chase them and kill any he could catch. And all too often he would succeed. Of course, when word got out around the district anyone passing that way would give the favoured spot a wide berth; but the killer soon realised that and found another equally good place on another path. As he was not expected there he played havoc for several days until his presence was known. But there were other paths and there were always natives going somewhere, and nobody knew where he was likely to be. He must be killed. (1959, p. 119).

*************************

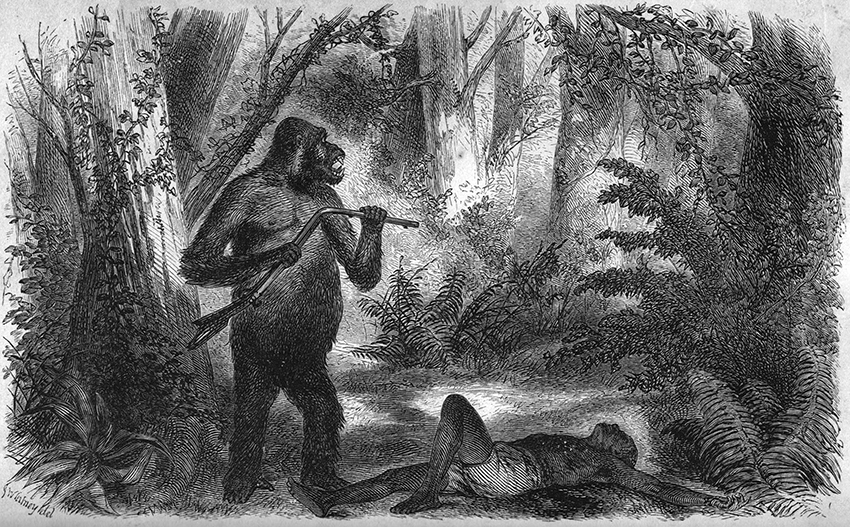

Paul Du Chaillu was a French Canadian who travelled to Africa (today’s Gabon) in search of adventure. He was probably the first European to see a Gorilla but his reports of this fabled animal were not at first believed. He made extensive travels inland and lived with various native tribes.

The onganga, or doctor, is a personage whose chief powers are the ability (which is real) to drink great quantities of the mboundou poison, and the power (which is imaginary) to discover sorcerers, and to confer powers on greegrees and charms, which, without his manipulations, are worthless. This personage enjoys, therefore, great consequence in his tribe or village. His word is potent for life or death. At his command–or rather at his suggestion–the village is removed: men, women, and children are slain or enslaved; wars are begun or ended. I was never able to satisfy myself on the interesting point on whether these doctors were themselves deceived; but after close observation and many trials, I concluded that they are in most cases. One or two I knew to be such great rascals that I felt pretty sure they were also humbugs; but the great majority were, I am confident, victims to their own delusions. (1861, p339).

***************************************

Eugene Marais grew up in South Africa and made a career as a journalist. His interest also extended to animals and he wrote a number of books and short stories about African life which I have listed in the Glossary. One of his specialties was white ants and he came to the following conclusion:

The most perfect example of the group soul can be observed in our own bodies. The human body is composed of a number of organs, each connected by a visible or invisible thread to the central point, the brain. Each organ is in constant activity and has a separate purpose–at least the purpose appears to be separate and independent; but on closer observation we find that all the organs are really working for a common purpose. The influence dominating all the organs come from one central point. In no single organ can we find a real independent purpose. After the composite physical body of a highly developed animal like man, there is no better example of the function of a group soul than the termitary. (1970, p. 50).

****************************

John Beams was an Englishman who went to work for the Indian Civil Service and served there till 1883. The following incident occurred in 1875:

A bright, clever, promising boy, named Atkinson, one of my Assistants was stationed at Kendrapara, a subdivision some thirty miles from Cuttack. He had been distinguished at a Public School (Harrow or Rugby, I forget which) and at Oxford, had passed high for the Civil Service, and during the short time he had served under me had shown signs of great ability and high promise. He had fallen in love with Florrie Faulkner, one of old Faulkner’s daughters and had arranged with her on his next visit to Cuttack he should ask her father’s consent. Some festivity—ball or something of the kind as we so frequently had—was to take place. I think it was on the occasion of the Queen’s birthday, which we always made a public holiday with some celebrations. He asked me for leave to come to Cuttack, which I granted. It was a blazing hot May day and he started early as usual and rode fast to get in before the heat began. At the very end of his ride, with the roofs and chimneys of Cuttack in sight, he had to cross the river which was then an expanse of dazzling sand about a mile broad, with a narrow stream of water trickling down the middle. The track across the sand was marked by deep ruts made by the cartwheels of the strings of carts that were constantly passing. This track wound up and down so as to cross the water at it shallowest, and Atkinson, anxious to get in, for the sun was already getting hot when he reached the river, seems to have tried to take a shortcut. But the narrow thread of water was treacherous. Though in general not more than a foot or two deep, in places it formed deep pools, where some furious eddy during the rains had scooped out the sand. Right into one of these he rode. His horse in its mad plunging threw him off, struggled to the bank and galloped away, but he never rose again. The Falkners had invited him to stay with them, and his servant had arrived with his luggage. They waited for him till one o’clock and then began to get anxious. Old Faulkner went to the door to look out and saw a policeman leading a riderless horse to the police lines. He stopped the man and recognised the horse as Atikinson’s. The man said that he had found the horse grazing by the road leading to the river, and was taking it, as unclaimed property, to the police station. When asked where the rider was, he stared after the manner of his kind and said he did not know. It had not occurred to him to consider the question. Faulkner came rushing over to my house which was close by, and I at once ordered out a strong body of police to go and search. On reaching the river bank the Inspector found numbers of men cutting grass for horses as usual. At that dry season the grass-cutters have to go long distances in search of green fodder and naturally seek it by the rivers. Questioned on the subject they all said cheerfully—Oh, yes! they had seen a sahib ride on the sand from the other side and try to cross the river. They saw that he had left the track and was heading for a deep pool and they saw him fall off the horse, and they saw the horse come out without him and gallop away. ‘Where is the Sahib?’ They did not know, perhaps in the water. ‘Did they not shout to warn him of his danger?’ No, it was no affair of theirs. ‘What did they do when they saw him fall?’ They? They cut grass for their horses!! Also there was a Kanungo riding on his pony with his servant following him. He saw the whole scene—and rode on to his work! He was quite close to the Sahib and saw that he was riding into danger, but it was no affair of his. (I promptly dismissed that Kanungo from the Government Service, at which all the natives, official and non-official, were very much surprised—and asked what he had done to be punished.)

We dragged the pool and found the poor boy’s body. He was quite dead. He was buried that evening and Florrie wept. She married another man a year after. (1961, p. 252).

********************************

Leonard Woolf, the future husband of Virginia Woolf, was at one stage an administrator in Ceylon. Here is a note from his diaries (1910):

In the afternoon put up 80 lots for sale from Warapitiya village. A large crowd present: in the middle of the proceedings the crowd parted and an old man with one side of his face shaved and the other side unshaven rushed into the ring and fell at my feet. He complained that the barber in the bazaar (and apparently the only one in Walasmulla) after shaving one half of his face had refused to shave the other unless he paid 50 cents. The price of a shave in Walasmulla is 5 cents. The barber was sent for and appeared accompanied by some hundreds of spectators. The decision was that he had to complete the shave and be paid nothing and that if he cut the old man he was to pay 50 cents. The operation was completed under a coconut tree in the compound before a vast crowd of spectators. The old man was in deadly earnest, the barber, who had the face of a rogue and a humorist said nothing but appeared vastly amused. This incident is typical of not a few of the ‘enquiries’ which take place on circuit in villages. (1963, p. 134).

***************************************

Lieutenant Colonel Jim Corbett was born in 1875, in Naini Tal, a hill station in India. His main employment was as a contract manager for the transport of coal for the Railways but he spent much of his spare time in fishing and hunting, including the hunting of man-eating tigers and leopards.

After an early tea that morning I announced that I wanted meat for my men and asked the villagers if they could direct me to where I could shoot ghooral (mountain goat). The village was situated on the top of a long ridge running east and west, and just below the road on which I had spent the night the hill fell steeply away to the north in a series of grassy slopes; on these I was told ghooral were plentiful, and several men volunteered to show me over the ground. I was careful not to show my pleasure at this offer and, selecting three men, I set out, telling the Headmen that if I found the ghooral as plentiful as he said they were, I would shoot two for the village in addition to shooting one for my men.

Crossing the road, we went down a very steep ridge, keeping a sharp look-out to right and left, but saw nothing. Half a mile down the hill the ravines converged, and from their junction, there was a good view of the rocky and grass covered slope to the right. For some minutes I had been sitting with my back to a solitary pine which grew at this spot, scanning the slope, when a movement high up on the hill caught my eye. When the movement was repeated I saw that it was a ghooral flapping its ears; the animal was standing in the grass, and only its head was visible. The men had not seen the movement, and as the head was now stationary and blended in with its surroundings it was not possible to point it out to them. Giving them a general idea of the animal’s position, I made them sit down and watch while I took a shot. I was armed with an old Martini Henry rifle, a weapon which atoned for its vicious kick by being dead accurate—up to any range. The distance was as near two hundred yards as made no matter and lying down and resting the rifle on a convenient pine-root, I took careful aim and fired.

The smoke from the black-powder obscured my view, and the men said that nothing had happened and that I had probably fired at a rock or a bunch of dead leaves. Retaining my position, I reloaded the rifle and presently saw the grass, a little below where I had fired, moving, and the hind quarters of the ghorral appeared. When the whole animal was free of the grass it started to roll over and over, gaining momentum as it came down the steep hill. When it was half-way down it disappeared into heavy grass, and disturbed two ghorral that had been lying up there. Sneezing their alarm call, the two animals dashed out of the grass and went bounding up the hill. The range was shorter now, and, adjusting the leaf sight, I waited until the bigger of the two slowed down, and put a bullet through its back, and as the other one turned and made off diagonally across the hill, I shot it through the shoulder.

On occasions one is privileged to accomplish the seemingly impossible. Lying in an uncomfortable position and shooting up at an angle of sixty degrees at a range of two hundred yards at the small white mark on the ghooral’s throat, there did not to be one chance in a million of the shot coming off, and yet the heavy lead bullet driven by black powder had not been deflected by a hair breath and had gone true to its mark, killing the animal instantaneously. Again, on the steep hill-side, which was broken up by small ravines and jutting rocks, the dead animal had slipped and rolled right to the spot where its two companions were lying up; and before it had cleared the patch of grass the two companions in their turn were slipping and rolling down the hill. As the three dead animals landed in ravine in front of us it was amusing to observe the surprise and delight of the men who never before had seen a rifle in action. All thought of the man-eater was for the time being forgotten as they scrambled down into the ravine to retrieve the bag.

The expedition was a great success in more ways than one; for in addition to providing a ration of meat for everyone, it gained me the confidence of the entire village. Shikar yarns, as everyone knows, never lose anything in repetition, and while the ghooral were being skinned and divided up, the three men who had accompanied me gave full reign to their imagination, and from where I sat in the open, having breakfast, I could hear the exclamations of the assembled crowd when they were told that the ghooral had been shot at a range of over a mile, and that the magic bullets used had not only killed the animals—like that—but had also drawn them to the sahib’s feet. (1952, p. 7–8).

I was lying on a ridge scanning with field glasses a rock cliff opposite me for thar, the most sure-footed of all Himalayan goats. On a ledge halfway up the cliff a thar and her kid were lying asleep. Presently the thar got to her feet, stretched herself, and the kid immediately started to muzzle her and feed. After a minute or so the mother freed herself, took a few steps on the ledge, poised for a moment, and then jumped down on to another and narrower ledge some twelve to fifteen feet below her. As soon as it was left alone the kid started running backwards and forwards, stopping every now and then to peer down at its mother, but unable to summon the courage to jump down to her for, below the few-inches-wide ledge, was a sheer drop of one thousand feet. I was too far away to hear whether the mother was encouraging her young, but from the way her head was turned I believe she was doing so. The kid was now getting more and more agitated and, possibly fearing that it would do something foolish, the mother went to what looked a mere crack in the vertical rock face and, climbing it, rejoined her young. Immediately on doing so she lay down, presumable to prevent the kid from feeding. After a little while she again got to her feet, allowed the kid to drink for a minute, poised carefully on the brink, and jumped down, while the kid again ran backwards and forwards above her. Seven times in the course of the next half hour this procedure was gone through, until finally the kid, abandoning itself to its fate, jumped, and landing safely beside its mother was rewarded by being allowed to drink its fill. The lesson, to teach her young that it was safe to follow where she led, was over for the day. Instinct helps, but it is the infinite patience of the mother and the unquestionable obedience of her offspring that enable the young of all animals in the wild to grow to maturity (1954, p. 115–116).

Download Corbett “Maneaters” in Pdf.

***********************************************

Derwent Heslop was born in England and his interest in engineering led him to take a position in Assam, in India, on a tea plantation. He then took a job building railways for India. Having a restless soul, and as railways were expanding world wide, he worked next in Columbia followed by China, Australia, and Ceylon. By this time the First World War had broken out and, joining the engineers, he rose to the rank of Major with most time spent in the middle east. He then took position in Ashanti and later Tanganyika before retiring in England. His only book, “Through Jungle, Bush and Forest”, is fascinating reading. He was twenty two years old on his first overseas employment when the following incident occurred:

I found that each bachelor had a native housekeeper to look after him, this being a custom in Assam since tea planting first started there. I know that my stay-at-home readers will be shocked at reading these lines but they purport to be a true account of my life in Assam, and if I suppress items like this what is the use of writing an account at all?

For the First three months I resisted any female addition to my household, but when a Nepali gentleman turned up at the bungalow one evening bringing his daughter, about seventeen years of age, to me, I bought the girl for Rs 50 from him; she became my “housekeeper,” and very well she looked after me, my servants, food and clothes. Moreover, she taught me the language in a very short time, so was a great asset to my work (1934, p.31).

*********************************

Major Claude Jarvis worked for the Egyptian Government as an administrator including the position of Governor of Sinai for fourteen years. He was fluent speaker of Arabic and studied the customs of the Bedouin Arab.

The Arab is sometimes called the Son of the Desert, but as Palmer said, this is a misnomer as in most cases he is the Father of the Desert, having created it himself….

There is definite proof that about a thousand years ago Sinai was reasonably wooded, with big tamarisk and thorny acacia trees, not to mention a variety of scrub bushes that grew to great size and covered a large area of ground. Both the tamarisk and acacia are disappearing rapidly, for the very simple reason that no young trees can possibly survive, as immediately they show above the surface they are bitten off by grazing goats, whilst existing trees are hacked to bits by Arabs who break off the branches to provide fodder to their animals….

In the vicinity of my garden in El Arish I have three acres of desert sand that has been enclosed for fourteen years and which, owing to the fact that it is protected from goats and camels, has become a dense mass of scrub bushes, some of them eight feet high with a diameter of twenty feet, whilst the soil between the growth is covered with a thick layer of rotten vegetation so that the sand is thoroughly stabilized and does not move against the strongest gales. This gives one an idea of what the Sinai must have been before the Arab came to lay it waste with its grazing flocks, and there is no doubt whatsoever that the responsibility for the sand dune area during the time I have been in the peninsula rests at the door of that accursed animal, the goat, ably assisted by his ruthless companion, the camel, and connived at by their feckless owner, the Bedouin Arab. (1936, p. 160–161).

In Wadi Gederiat:

“The partridges do not produce enough children,” he said to me one day, “and it is not the fault of the females. There was a nest over there with sixteen eggs in it, but only four hatched.

“Wallahi, no,” replied Hussein; “she sat as tight as if she were an Egyptian Government clerk in a chair. It is the male’s fault; he is old and mush nafi (useless), but he walks about like an old Pasha with a harem and won’t give the young chicks a chance. He thinks he is good enough for ten hens and he isn’t good enough for one. What you should do is shoot all the old big cocks in the ailets (conveys), and then the young cocks will see to it that there are children.

I followed Hussein’s advice, and at the end of that season set out on an old cock slaughtering expedition. It was quite easy to spot the sultan of each convey, for he was nearly one third as large again as the ordinary birds and had an aggressively bid head; and Hussein was right in his denunciation, for these old birds kept the conveys together and refused to allow the young males to pair off. I managed to account for ten in one most exhausting day. The result the following year was amazing; for several pairs were seen with twelve or fourteen chicks, and the establishment of the Wadi Gedeirat shoot owed much to Hussein’s discernment in discovering the cause of the paucity of numbers.

Hussein and Suliman had their tents just outside the wadi, and my wife used to call there whilst I was shooting to hear the latest news of the Arab world. Both these little old gentlemen had young and virile wives ― probably the third or fourth editions ― and when these ladies heard from my wife exactly what I was doing that day with the old cocks, and the reason for it, they screamed with laughter and pushed each other about.

“And Hussein told the Bey to that, did he?” said Fatima, shaking with mirth. “Do you hear that ya Amina? Hussein says the cock partridges are too old to be married, and look at us both without children. Wallahi, if the Bey thinks that way, the first thing he ought to shoot are Hussein and Suliman.” (1942, p. 110–111).

***************************************

Lieutenant General Sir John Glubb was a British Military officer who served in the First World War. In 1920 he transferred to Iraq where he was responsible for suppressing tribal rebellions. In 1926 he became to be an Administrative inspector for Iraq. In 1939 he was instrumental in strengthening the Arab Legion and was commander of this army during the division of Palestine in 1947 into Arab and Jewish areas. The Israelites are essentially an Arab tribe as has been show by modern DNA analysis.

About 1250 B.C., a nomadic tribe known as Beni Israil, or the children of Israel, invaded Canaan, the modern Palestine. Canaan had been a civilized and settled country for many thousands of years, whereas the Israelites were simple, ignorant tribesmen who had been living as shepherds on the eastern side of the Nile Delta.

Where, however, there was no regular imperial army, towns and villages were at a hopeless disadvantage. A nomadic tribe moved as a single unit, with its tents and flocks, and could capture towns and villages one by one, massacring the inhabitants, a process constantly repeated in areas bordering on the desert, in Palestine, Syria or Iraq.

Having thus killed all the people of Jericho and other towns, the Israelites received the submission of the towns and villages along the range of mountains from Hebron to Galilee. At the same time, the Philistines, a people from the Aegean, landed on and conquered the coastal plain, confining the Israelites to the mountains.

As tented nomads, the Israelites did not become villagers or farmers, but merely landlords who collected tribute from the people of the land. To imagine that the people of Canaan after the time of Joshua were all Israelites is erroneous. The latter were nomad warriors who imposed themselves on a comparatively cultured people and obliged them to pay tribute. They divided the country between tribes, not as landowners but as landlords. The number of invading Israelites was about 15,000. (1983, p. 132).

***************************************

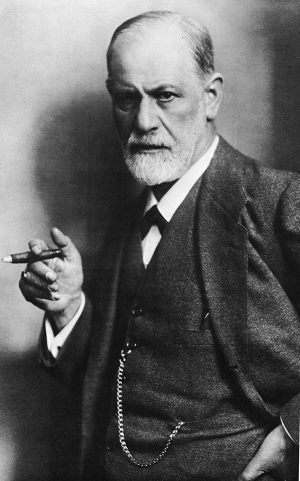

Sigmund Freud was also a student of religion as well as psychoanalysis. He suggests here that the first Moses was an Egyptian and lived around the 13 or 14 century B.C. (p. 22-29). The Egyptian pharaoh at the time was Amenhotep (IV) who rejected the polytheism of the previous pharaohs and adopted monotheism during his reign of 17 years. He changed his name to Ikhraton, left Thebes and built a new capital further down the Nile (p. 38–39) which he called Akhetaton. Nefertiti was his wife. It was during this period that Moses lived and he embraced this new religion with Aten his god. Not wanting to abandon this new religion and revert to polytheism upon the pharaoh’s death, Moses and his Egyptian followers (Levites) selected the repressed Semitic tribes of Egypt to leave with him and this departure became the Exodus (p. 47). These various tribes with their new Egyptian religion crossed the Sinai and settled in the Hejaz. Over some hundreds of years and under a new Moses they lost their Egyptian religion and gained the polytheistic religion of the Arabic Midianites (p. 55) of which one of the gods, the volcano god, was called Jahve (origin of John, Jahweh, Jehovah and so on). Jahve recognised the existence of other gods and was jealous of them. But over time the repressed monotheism of the lost Egyptian religion came to the fore and reasserted itself and so Jahve became the only god with all other gods now false gods. Thus the Jewish religion has as its origin both Egyptian and Arab components.

This brief summary does no justice to Freud’s book ‘Moses and Monotheism’ but the reasoning and analytical skills of Freud are impressive and this book should be read by anyone with an interest in religion.

However, I have some difficulty with the term “monotheism”. The ancient Greek gods distinguished themselves from ordinary people by being immortal, and so we could expect that the “God” of the Semitic religions would also be immortal. It must further follow that the devil (whether fallen angel or not) would also be immortal otherwise this duality of good/bad would collapse were the devil to die. The devil then, must also be a god, albeit a bad one. This reasoning gives the Semitic religions at least two gods.

*****************************

Isabelle Williamson and her husband were missionaries in China and witnessed the same debt to myth as was common in Africa and other parts of the world. The desire to believe in myth appears a universal characteristic of humankind. We are still not free from this debt. The myth that there is an afterlife upon death is still widely believed today yet this belief has no biological basis. The biology texts of the world’s schools say otherwise. While this belief may be on the wane, it still persists.

In the afternoon we passed a newly dug canal, where a number of soldiers were busy driving piles for a bridge. They had erected an immensely high trestle scaffolding, which would have been a credit to any trestle bridge railway contractor in America. This scaffolding was to enable them to drive the piles. Probably, under each large pile would be put a living child ─ under the piles on the west, boys; under those on the east, girls. Alas! that men with brain enough to plan and execute engineering works of great magnitude were yet so dark with superstition as to believe that the bridge would have small chance to stand unless supported by this sacrifice of human life. Near Chefoo we knew of eight children being so sacrificed. A wooden bridge had been frequently swept away by the turbulent stream, so that, to appease the spirit of the river, this sacrifice was thought necessary. The families from which the children were taken were poor. Each family got a handsome douceur, and the affair was quietly managed. I am only sorry to add that the bridge, being constructed of heavier timbers, stands still, and the people are satisfied that they have done right. Children so sacrificed are supposed to enjoy freedom from punishment in after life; and the sacrifice of them is considered a meritorious act on the part of their parents, so there is no need to mourn. Afterwards, when telling the number of children, they never count the ones that perish thus. (1884, p. 174–175).

Torture of young girls through foot binding seems similar to the various types of repression of women today. The perversions of an emperor caused ten centuries of pain to countless millions of young girls.

The fact that all the empresses of the Manchu dynasty have large feet is too frequently overlooked. Another anomaly in this empire, where so many customs are contrary to Western lands, is that whereas royalty in Europe leads the fashion, here it fails, and the pei sing, the ‘hundred families,’ carry the day according to their own whims.

A most serious whim this is. The process begins in the child’s fifth year. The little foot is taken by the mother, the four toes, leaving the great toe free, are pressed down completely under the sole: a bandage seven feet long and about an inch and a half wide is used. This bandage is wound over the toes, and crossing the foot is passed around the heel. The strength of one woman is not considered sufficient, so another stands behind and pulls at the bandage. It is wound over the toes and around the heel till the whole seven feet of cloth is expended. The bandage is tightened day after day till the foot acquires the desired shape and smallness. This process is continued for years, and the pressure is never relaxed.

There are three degrees of compression. The first is adopted by some of the very poor peasant women, who expect their daughters to have hard work, when the foot is not quite destroyed. The second degree is most common, and in Shan-tung almost every woman of the middle class, and many of the poor, endure it. The bandage is drawn so tight as to make the foot a shapeless mass; the toes are so pressed into the foot as to almost obliterate them, unless indeed they become diseased and require treatment. The third degree is not often practiced. In this case the foot is desired to be so small that the great toe is also curved down under the sole.

The cramping entails great suffering. I have always found the little feet hot and painful till the girl has attained her full growth. While some women say they did not experience much pain, most tell me that at intervals it was excruciating torture. I have often found young girls rocking themselves to and fro, evidently in extreme suffering because of the bandage.

Besides, in many ways destroying the health it shrivels the leg, and often produces serious disease in the foot itself. Diseased bone in the instep has often been treated in the hospital at Chefoo. Sometimes the toes fester. Frequently the women would come to the hospital suffering so much that that they implored me to amputate the painful toes. After a while, finding that they could thus obtain relief from pain, they came in great numbers. (1884, p. 214–216).

Binding the feet and the pain that went with it would focus a woman’s attention on that part of the body so the following question is forgiven:

Next day in the dewy morning we set out — according to arrangement — to visit the great temple. It stands to the west of the great gate, and there, under a veranda, were assembled quite a crowd of ladies with their attendants. Two of the elderly ladies of the family and four attendants, who were also related to the duke’s household, came at once to meet me and escort me over the temple. We had a pleasant morning. I found them most companionable and intelligent. We talked of many matters of Chinese interest and they questioned me on many things relating to England. Queen Victoria was a favourite question.

“What size are her feet ?” was the first question. (1884, p. 148).

***************************************

Timothy Richard was a Welsh missionary in China and was the originator of the idea of the United Nations. He foresaw that a federation or League of Nations was necessary to advance world peace. He put the idea to a number of nations, including Britain and China. In 1906 he visited President Roosevelt and “whilst President Roosevelt was not prepared to take any action himself, he stated that if the Chinese Government would send a special envoy to discuss the matter he would give it careful consideration” (1916, p. 373). The following is from the author’s log while traveling in Shensi.

January 28, 1878.

Started on a journey south through the centre of the province to discover the severity of the famine. I rode on a mule, and had a servant with me, also on a mule.

Before leaving the city we could not go straight through the south gate, as there was a man lying in the street about to die of starvation, and a crowd had gathered round.

January 29thth. 140 li south.

Passed four dead men on the road and another moving on his hands and knees, having no strength to stand up. Met a funeral, consisting of a mother carrying on her shoulder a dead boy of about ten years old. She was the only bearer, priest, and mourner, and she laid him in the snow outside the city wall.

January 30th. 270 li south.

Passed two men apparently just dead. One had good clothes on, but had died of hunger. A few li farther on there was a man of about forty walking in front of us, with unsteady steps like a drunken man. A puff of wind blew him over to rise no more.

January 30th. 290 li south.

Saw fourteen dead on the roadside. One had only a stocking on. His corpse was being dragged by a dog, so light it was. Two of the dead were women. They had had a burial, but it had consisted only in turning the faces to the ground. The passers-by had dealt more carefully with one, for they had left her her clothes. A third corpse was a feast to a score of screaming crows and magpies. There were fat pheasants, rabbits, foxes, and wolves, but men and women had no means of living. One old man besides whom I slowly climbed a hill said most pathetically: “Our mules and donkeys are all eaten up. Our labourers are dead. What crime have we committed that God should punish us thus?”

In the midst of such universal suffering, the wonder was that there was no robbery of the rich. But to-day this was explained, for there were notices put up in the villages saying that by order of the Governor, if any persons attempted robbery and violence, the head men of the town or village were empowered to put the robbers to death at once. The result was a wonderful absence of crime. The only tears I saw shed by the patient suffers were those of the mother burying her boy.

February 1st. 450 li south.

Saw six dead bodies in half a day, and four of them were women: one in an open shed, naked but for a string round her waist; another in a stream; one in the water, half exposed above the ice at the mercy of the wild dogs; another half clad in rags in one of the open caves at the roadside; another half eaten, torn by birds and beasts of prey. Met two youths of about eighteen years of age, tottering on their feet, and leaning on sticks as if ninety years of age. Met another young man carrying his mother on his shoulders as her strength had failed. Seeing me looking at them closely, the young man begged for help. This is the only one who begged since I left T’ai-yuan fu.

Saw men grinding soft stones, somewhat like those from which stone pencils were made, into powder, which were sold from two or three cash per catty (1 1/8 lb.) to be mixed with any grain, or grass seed, or roots and made into cakes. I tried some of these cakes and they tasted like what most of them were—clay. Many died of constipation in consequence of eating of them.

Three brothers who were colliers died one after the other, the first twenty days ago. For burial he was placed in two large jars, one enclosing the upper part of the body, the other the lower. Seven days later another brother, but there was no more jars, and the corpse was left on the floor. The third brother was so weak that when I gave him money to help bury the dead, he could not leave his k’ang. Soon another who heard of my relief came to me to say that they had unburied dead in every house.

Saw another woman trying to rise. She had had the strength to life one leg, but no strength to stand up. Father on I saw two heads in one cage, a warning to those who would attempt violence.

February 2nd. 530 li south.

At the next city was the most awful sight I ever saw. It was early in the morning when I approached the city gate. On one side of it was a pile of naked dead men, heaped on top of each other as if they were pigs in a slaughter house. On the other side of the gate was a similar heap of dead women, their clothing having been torn away to pawn for food. Carts were there to take the corpses away to two great pits, into one of which they threw the men, and into the other the women.

Outside the north gate of Hengtung there were three dead, a boy and, apparently, his father and grandfather, side by side. Snow had fallen the night before. On the snow there were the marks of what had been a struggle between two men, and blood was mingled with the snow — a sign that it was not safe to travel alone, although there were two human heads hung up in cages on two separate trees as a warning to evildoers. For many miles in the district the trees were all white, stripped clean for ten or twenty feet high of their bark, which was being used for food. We passed many houses without doors and window-frames, which had been sold as firewood. Inside were kitchen utensils left untouched only because they could not be turned into money. The owners had gone away and died.

February 3rd. 600 li south.

Saw only seven persons today, but no woman among them. This was explained by meeting carts daily full of women who were being taken away for sale. There were travellers on foot also, all carrying weapons of defence, even children in their teens, some with spears, some with bright, gleaming swords, others with rusty knives, proofs of their terrible plights. We did not feel very safe in their midst.

February 4th. 600 li south.

Stopped at Siang Liu. Met forty carts from Pu Chow fu going south for grain. Here were effigies of men on one side of the street. On the opposite side of the street were written two big characters, “Poor people” mute appeals to all who passed by. Heard of stories at the inn that night of parents exchanging their children as they could not eat their own, that men dared not go to the pits for coal as mules, donkeys, and their owners were all likely to be killed and eaten .

Having gone so far, and seeing such terrible sights, I decided to return to T’ai-yuan fu, as I had sufficient proofs of the horrors of famine to move even hearts of stone (1916, p. 129–133).

Download “Timothy Richard” in Pdf.

***************************************

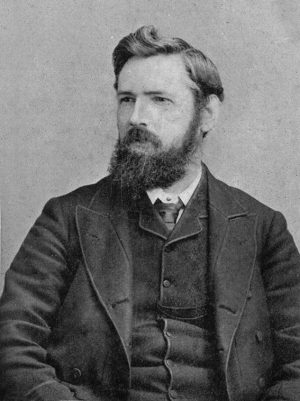

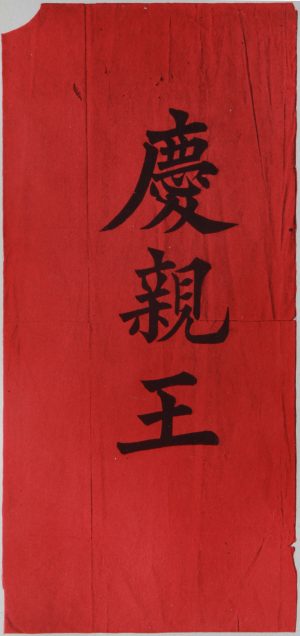

Prince Ching’s calling card.

Famine came regularly to provinces such as Shensi and there appears to be boom and bust cycles as could be expected naturally in non-human animal populations. Francis Nichols, an American, travelling through a neighbouring area to that of Richard above 25 years later writes of a different famine.

With the continued desolation in their fields, the farmers began flocking into Sian. During the winter of 1900–01 more than 300,000 villagers, desperate and starving, made their way to the capital of the province. Owing to a fear of bread riots, the Governor did not allow them within the city walls. The famine suffers were compelled to live in fields in the suburbs. For shelter they dug caves in the clay banks by the side of the road, and they made their death lingering by eating coarse grass and weeds. All around Sian when I visited it were these grim, blackened caves. According to native statistics 130,000 perished from hunger in one suburb. On the morning of each day for three months more than 600 bodies were collected by the governor’s servants, and were buried in a field near the eastern gate. As a result of famine-conditions a disease that seemed a combination of dysentery and cholera broke out in Sian, causing the deaths of hundreds of residents of the city, who had escaped the worst rigours of hunger.

And all the time food was becoming scarcer. By-and-by human flesh began to be sold in the suburbs of Sian. At first the traffic was carried on clandestinely, but after a time a horrible kind of meat ball, made from the bodies of human beings who had died of hunger, became a staple article of food, that was sold for the equivalent of about four American cents per pound. The trade in human flesh had assumed considerable proportions before it was summarily stopped by Tuan Fang, the Governor, who cut off the heads of three men who dealt with it.

Tuan Fang appointed a relief committee, whose members were prominent merchants and bankers of the city. They opened thirty-two soup kitchens in Sian for the hungry in the suburbs. From the mandarins the committee obtained list of destitute families. The committee had charge of the 3,000,000 taels contributed from the native sources during the three years of famine. The money came from the Imperial treasury in Peking, from the Shensi provincial funds, and from Chinese charitable societies. The relief funds were further augmented by the sale of degrees. That the government should resort to such a step is proof of the straits it had been reduced in contending with the hunger-cloud which overhung the country. Under ordinary conditions it is sometimes possible for a man to obtain his degree by bribing an official who conducts the examination, but, however it may be obtained, a degree is absolutely essential for an appointment as a mandarin. At the direction of the governor, degrees in Shensi were offered, without examination, to anyone who would pay a certain amount to the famine-fund (1912, p. 230–231).

**********************************************

Mildred Cable and two sisters, Eve and Francesca French, travelled extensively in China as Christian missionaries. Their adventures were numerous and their many books give a idea of the lawlessness of north west China where petty lords, governors and generals fought for control.

“How far from the city are these caves?” we enquired.

“Only forty-five li,” was the answer.

“What kind of road is it?”

“Passable. You have good mules. They will manage it all right, and at the caves you will find guest-house, stabling and kitchen, and the Abbott Wang knows about you and will see that all is done for your comfort”…..

At the exact limit of the area of irrigation we stepped out on to the gravel plain and faced desert once more. The line of dwindling sandhills showed the direction, but the track itself was hard to trace, and on the various occasions we went to the Caves of the Thousand Buddhas I do not think we ever followed the same course twice.

We were on our way to see something that was very ancient, a place where men of one age make contact with those of another. A thousand years or more lay between them and their work and us and ours. (1954, p. 44).

***************************************

Lawlessness and corruption characterised many countries and Peru and Columbia were no exception at the end of the 19th century. W.E. Hardenburg, a young America, was recruited to investigate the injustices of the rubber industry along the Putumayo river by a company set up by a Peruvian man; Julio Cesar Arana. This company was eventually registered in London in an attempt to give it credibility. It was estimated that Arana’s reign of terror caused the deaths of some 30,000 Indians. Despite many reports, investigations and other delays, (in 1910 the Foreign Office sent Roger Casement who confirmed Hardenberg’s report) nothing was ever done to stop the method of rubber collection and Arena died naturally at the age of 89.

As each Indian’s name is called he steps up and delivers the Indian rubber he has collected, which is weighed on the spot. Occasionally a kilogram or two are lacking, and in this case the Indian is given from twenty-five to one hundred lashes by the Barbados negroes, who only for this purpose ─ have been brought here. At about the tenth blow the victim usually falls unconscious from the effects of the intense pain.

Sometimes two or three Indians and their families do not appear on account of not being able to collect the amount of rubber assigned to them. In this case the chief of correria orders four or five of his agents to collect ten or twelve Indians of a tribe hostile to the fugitives and to set out in pursuit of the poor wretches, their capitán being dragged along, tied up with chains, to act as a guide to reveal their hiding place, and being threatened with a painful and lingering death in case he does not find them. After some search the hut where they have taken refuge is found and then takes place a horrible and repugnant scene. The hut constructed by the refugees is of thatch, of a conical form and without doors. The chief orders his men to surround the house, and two or three of them approach and set fire to it. The Indians, surprised and terrified, dash out, and the assassins discharge their carbines at the unfortunate wretches. The men killed, the bandits turn their attention to the rest, and the old, the sick, and the children, unable to escape, are either burned to death or are killed with machetes (1912, p. 208–209).

***************************************

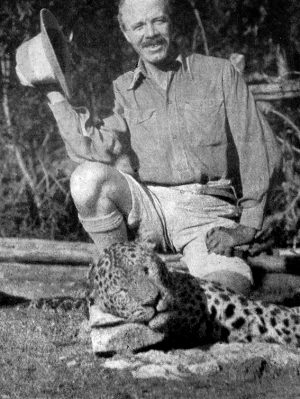

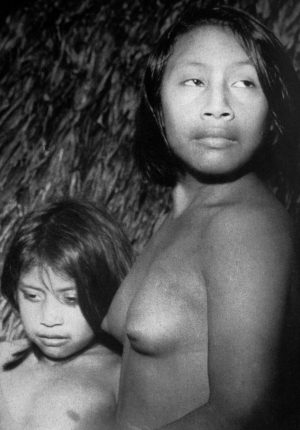

Garavini was an Italian who went to Venezuela in search of diamonds. He ventured into the interior and befriended a native tribe. He married three sisters and learnt their language. He endured rainy seasons, jaguar attacks, insects, and disease but eventually made a fortune from diamonds.

Women got married when they were about nine or ten, and if they had sisters these too became wives of the eldest one’s husband, and moved into his hut. Sometimes a bride’s sisters were mere infants, and on more than one occasion I heard a man say, pointing to a tot of some two or three: ‘She my wife. Me bring her up.’